The news that Gov. Jerry Brown appears to have mostly gotten his way on school funding changes is likely to be presented as a dramatic victory for the people who believe helping struggling English learners is the key challenge facing California education.

But it’s one thing to believe that this is the key challenge, as I do, and another thing entirely to think that what’s being done in response will work or result in significant change. Why the skepticism? Here goes:

Combine unproven theory and confused governor …

1. The proposal builds off the belief that school quality is a function of school spending. If that were true, than schools would have gotten much better in the last 30 years. The 1983 “Nation at Risk” report triggered the modern education reform movement and yielded a big boost in per-pupil, inflation-adjusted spending. It hasn’t led to the broad gains this simplistic theory would yield, and often hasn’t resulted in any progress at all.

1. The proposal builds off the belief that school quality is a function of school spending. If that were true, than schools would have gotten much better in the last 30 years. The 1983 “Nation at Risk” report triggered the modern education reform movement and yielded a big boost in per-pupil, inflation-adjusted spending. It hasn’t led to the broad gains this simplistic theory would yield, and often hasn’t resulted in any progress at all.

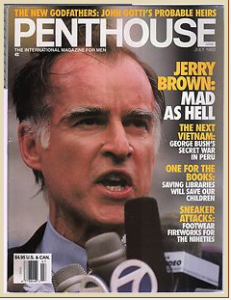

2. Even if school officials come up with promising ways to bring improved instruction to struggling English learners, they could be undercut by Gov. Jerry Brown’s incoherent, ad hoc education policies — policies that are painful in their naiveté about what happens when school boards are “empowered.” As noted here before, the governor believes …

“… more money and ‘subsidiarity’ — essentially, smart and thoughtful local control — are the keys to improving schools. The governor was asked why he thought local control would work better than it did before the reforms triggered by the “Nation at Risk” report in the 1980s and No Child Left Behind in the 2000s, given that a key factor driving those reforms was that local control often led to a focus on adult employees instead of on students.

“Brown responded by ridiculing ‘top down’ policies that presumed people in Washington or Sacramento are wiser than ‘the teacher, the principal, the superintendent and the school board.’

“This is a talking point, not a policy. … When unions run school districts, ‘top down’ education policies are often the only way to protect the interests of students.”

… with intransigent unions and you don’t have a encouraging picture

3. Even if school officials come up with promising ways to bring improved instruction to struggling English learners, they could be undercut by the union power that Jerry Brown either ignores or is oblivious to.

3. Even if school officials come up with promising ways to bring improved instruction to struggling English learners, they could be undercut by the union power that Jerry Brown either ignores or is oblivious to.

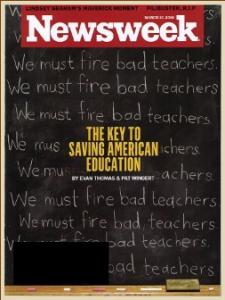

The example of the Stull Act can’t be brought up enough. A 1971 state law requires that student performance be part of teacher evaluations. It doesn’t say it may be. It says it must be. Yet the law was simply ignored in most California districts until 2012, when a successful lawsuit forced Los Angeles Unified to begin, yunno, following state law.

You’ve heard of jury nullification. The is local teacher union nullification. Instead of honoring a clearly written state law, school district after school district has adopted teacher evaluation processes that routinely result in 99 percent of second-year teachers getting tenure and that conclude nearly all teachers are above average or downright great.

So when the state budget is passed on Friday, and the back-slapping begins about the new era in California education, feel free to groan. The success of the new funding formula depends on a simpleminded theory about school quality that has 30 years of history going against it. It depends on the follow-through of a governor who offers incoherent and contradictory comments about education. And it depends on the cooperation of teacher unions who have a history of not giving a damn about struggling students — at least if it means teachers will be judged on how much they actually help those struggling students.

Crossposted on CalWatchdog