Editor’s Note: Part 2 of the ‘Boom, Bust, Repeat?’ Series, which explores how the state can smartly manage recent revenue gains to strengthen public programs for the long-term.

A few weeks after Tax Day—and only a week before the governor releases his revised May budget—California finds itself in an enviable position.

After years of cuts and fiscal strain during the Great Recession, the recovery is finally at hand: In March, California employers were responsible for one out of every three new jobs in the country and with tech and other industries expanding, revenues are climbing as much as $4 billion more than expected.

If a boom on this scale feels unprecedented, it’s not. As CA Fwd’s Lenny Mendonca and Pete Weber pointed out, California has been here before—quite a few times: “In hindsight, many of the state’s biggest fiscal challenges are the consequences of decisions made at moments exactly like this one.” In a blog series called Boom, Bust, Repeat?, CA Fwd is highlighting how state leaders can learn from the state’s rocky fiscal past—and use this year’s budget to lay a foundation for long-term prosperity.

The first step, prepare for the next dip

While lawmakers are pondering ways to funnel a portion of this year’s revenue windfall into state programs, Mendonca and Weber offer a word of caution: “The average time between the last five recessions was 68 months. May 2015 is the 71st month of economic growth.”

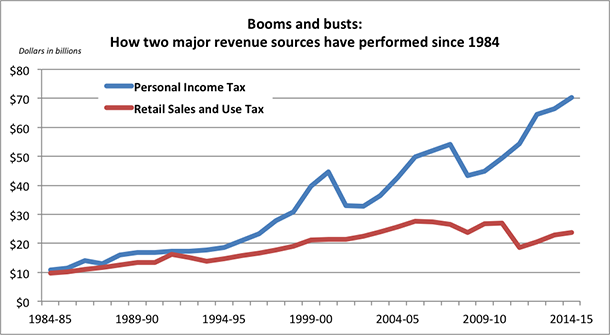

It may be a year or two, but the economy will dip again. And when it does, the state’s still-unstable revenue system—more dependent than ever on volatile personal incomes of the wealthiest Californians—will dip with it.

And typically revenue comes down the way it went up. Remember 2005? In the May Revision that year, revenues came in $5.5 billion ahead of the amount approved in the 2004 budget. By the next year, they were up $10 billion. What did the Legislature and Governor do? They spent this temporary windfall on ongoing programs—boosting spending in health and human services over three budgets from $24 billion to $29 billion and K-12 education from $37 billion to $42 billion.

Using an economic boom to increase baseline spending on safety net programs and schools is certainly an understandable choice, but while the economy expanded, lawmakers also shrugged off calls to pay off the state’s billions in budgetary debts—or to rein in the state’s growing pension obligations. Then, in the midst of this spending spree, the worst recession in California’s history arrived, creating a multi-year deficit over $40 billion.

How could anyone have seen a boom on that scale followed by such a dramatic bust?

It shouldn’t have been that hard: The state had experienced basically the same scenario only a few years before, when the late-1990s tech bubble drove up revenues enough to boost the K-12 budget by $5 billion over two years. In those years, too, lawmakers spent as if these resources were a “new normal,” cutting the car tax—eliminating a local revenue source worth $4 billion a year—and granting billions of dollars in retroactive pension boosts to state employees.

When that bubble popped, income taxes plummeted 20 percent—leading to what were then the largest spending cuts since World War II. Total spending fell $17.5 billion and the state found itself struggling to address a $38 billion budget gap, which it closed with drastic cuts to schools and social services—and $10 billion in what was referred to as “deficit financing,” borrowed money that lingered on the state’s books for years. Unfunded pension and health care obligations have now grown to $171 billion.

Meanwhile, to keep local governments whole, the car tax cuts were backfilled out of the state General Fund, creating an ongoing budget obligation that has grown to $6 billion a year. That is, of course, more than was generated by the original tax, which was viewed as both fiscally stable and admirably progressive.

A new year and a new opportunity

A new year and a new opportunity

This time around, it can be different. And it must be different.

The pressure to ignore the lessons of the past will be even stronger in this cycle because of Proposition 30—the temporary taxes on Californians making over $250,000 a year, which are now responsible for $8 billion of the $113 billion in the General Fund. These revenues, which provided an enormous—and important—boost to schools and safety net programs when the state was emerging from the recession, will start to phase out next year, taking billions of dollars off the table.

As lawmakers consider how to build a budget at what may be the peak of the business cycle, lawmakers would also be wise to remember 1978. That spring, too, surpluses rolled in to state and local governments —including inflation-fueled property taxes. Californians, persuaded that they were overtaxed, were offered only one solution: Proposition 13, a tax measure that has impacted every state and local budget for nearly 40 years.

As CA Fwd is highlighting in Boom, Bust, Repeat?, there are certainly ways to avoid these budgetary mistakes of the past—using a portion of what are likely one-time resources this year to hold down future costs, for example, and prepare the budget for the next recession.

But the first step is to start with thinking of this year as a boom—some of which will eventually go bust.

Originally published at California Forward.