The City of Berkeley is working on a plan to issue a cryptocurrency municipal bond to fund affordable housing. A February 7th press release said the city was working with municipal finance startup Neighborly.com and Cal’s Berkeley Blockchain Initiative to “develop a first-of-its-kind tokenized municipal bond compliant with all regulatory requirements.” While this new innovation might ultimately benefit local taxpayers, crucial details are missing, and the plan could worsen the city’s already tenuous finances.

Without legislation or bond offering documents, it is not clear exactly how the so-called “tokenized municipal offering” might work. The city is unlikely to follow in the footsteps of Nishiawakura, a Japanese village that is reportedly considering an Initial Coin Offering (ICO). The village would sell new cryptocurrency tokens for Japanese Yen and then spend the proceeds on local infrastructure. But a Berkeley municipal ICO would likely run afoul of the Securities and Exchange Commission which has been highly critical of cryptocurrency offerings. So, instead, Berkeley’s cryptocurrency would somehow be tied to a new municipal bond offering.

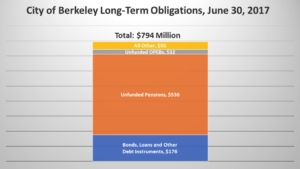

And, while an ICO would not necessarily add to Berkeley’s tremendous debt burden, new municipal bonds would. According to the city’s most recent Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Berkeley has almost $800 million in long-term obligations. This works out to $6500 for each city resident, and comes on top of federal, state, county and special district debts that local taxpayers are obliged to service.

As the accompanying chart shows, most of Berkeley’s debt takes the form of unfunded pension and retiree healthcare obligations. And, because lion’s share of city pension obligations is discounted at an aggressive 7.65% rate, the amounts shown here arguably understate the real burden.

The cost of covering these obligations threatens to crowd out other city spending priorities. Pension and OPEB contributions in Fiscal Year 2016-2017 cost the city $47 million or 14% of overall spending. A strong local economy powered the city to a large government-wide surplus for the year, but these public employee retirement costs will weigh quite heavily when the next downturn inevitably arrives. Further, because Berkeley is a member of CalPERS it will face rapidly escalating pension contributions in the coming years as the pension behemoth lowers its assumed rate of return and tries to pay down unfunded liabilities. According to CalPERS data analyzed by Reason Foundation, Berkeley’s contributions are projected to rise 85% between now and 2024-25.

So city officials would be wise to pay down Berkeley’s debt in these flush times rather than looking for innovative ways to borrow. But the mayor and city council want more resources to pay for affordable housing. Like much of the San Francisco Bay Area, Berkeley is confronting steep housing costs and widespread homelessness in its downtown.

Elected officials see the new type of bond as a way to push back against a federal government that is pressuring sanctuary cities and reducing incentives to produce affordable housing. Because the new tax law is lowering corporate tax rates from 35% to 21%, companies will have less reason to take advantage of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits. Consulting firm Novogradac estimate that the tax law will reduce affordable housing construction by up to 235,000 units nationally over the next ten years.

Of course, only a small and uncertain proportion of that loss would apply to Berkeley especially because the city’s Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance restricts multi-family housing development in large swathes of town. Rather than borrow money to build new housing, the city might instead relax its zoning restrictions to enable private builders to create new units for all income levels. Further, local politicians should also look at the city’s rent control laws, which likely restrict the availability of older housing stock for residential rentals.

East of the Pacific Coast, many US cities balance housing supply and demand without issuing crypto-bonds. Rather than break new ground and break taxpayers’ backs, Berkeley officials should consider deregulatory approaches to increasing private housing supply.