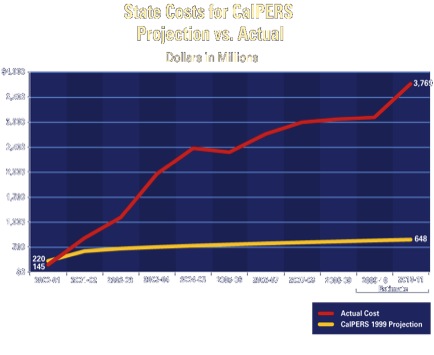

Some public pension funds like to blame the 2008 stock market crash for the pension cost crisis but as the chart below shows, pension costs started rising well before the 2008 stock market crash.

In fact, those pension costs increased sharply through the decade even though CalPERS and other public pension funds earned money for the period including the 2008 crash. This is because public pension costs rise whenever public pension funds earn less than they expect to earn. Put another way, when it comes to pension costs, what matters is the "spread" between expected returns and actual returns.

When pension promises are made, employers and employees make contributions into pension funds. The size of those contributions is based upon an expected return from investment of those contributions so that, together, the contributions and investment earnings on those contributions are supposed to be enough to pay the pension when it’s due. The higher the expected investment return, the lower the contributions when the promises are made. But if the actual investment return falls short of the expected return, the employer must make up all the difference.

This is why the state had to inject an extra $20 billion into CalPERS over the last ten years even though CalPERS earned money during that period (its actual return was roughly 40% of its expected return). In fact, even if the stock market was still at its pre-crash peak of more than 14,000, the state would still be suffering billions in extra pension costs because the market would have to be above 25,000 by now for CalPERS to have met its expected investment return. Instead, the market is below 11,000.

Going forward, CalPERS expects to require $270 billion from the state over the next thirty years. However, that projection is based upon an expected return that implicitly forecasts the stock market to double every ten years. Anything less and state costs will be higher. Also, because pension liabilities are so long-term in nature (people working today will be getting pension payments 50-60 years from now), it’s the long-term spread that matters. One year up or one year down doesn’t count as much as does the long-term positive or negative spread.

So, don’t let pension funds fool you. When it comes to pension costs, keep your eyes on the spread.