The revival of America’s core cities is one of the most celebrated narratives of our time—yet, perhaps paradoxically, urban progress has also created a growing problem of increasing inequality and middle-class flight. Once exemplars of middle-class advancement, most major American cities are now typified by a “barbell economy,” divided between well-paid professionals and lower-paid service workers. As early as the 1970s, notes the Brookings Institution, middle-income neighborhoods began to shrink more dramatically in inner cities than anywhere else—and the phenomenon has continued. Today, in virtually all U.S. metro areas, the inner cores are more unequal than their corresponding suburbs, observes geographer Daniel Herz.

Signs of this gap are visible. Homelessness has been on the rise in virtually all large cities, including Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco, even as it declines elsewhere. Despite numerous exposés on the growth of suburban poverty, the poverty rate in core cities remains twice as high; according to the 2010 census, more than 80 percent of all urban-core population growth in the previous decade was among the poor. For all the talk about inner-city gentrification, concentrated urban poverty remains a persistent problem, with 75 percent of high-poverty neighborhoods in 1970 still classified that way four decades later.

Clearly, then, the urban renaissance has not lifted all, or even most, boats. San Francisco, arguably the nation’s top urban hot spot, is seeing the most rapid increase in income inequality of any metropolitan area in the nation, according to a Bloomberg study. The ranks of the country’s most bifurcated cities include such celebrated urban areas as San Francisco, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, where the poverty rate is higher now than before the 1992 riots, both in the city proper and in the riot zone.

The new urban demographic—a combination of poor residents, super-affluent households (many childless), and a younger generation with limited upward mobility—has created conditions peculiarly ideal for left-wing agitation. This marks a sharp contrast with the early 1990s, when urban voters embraced pragmatic mayors like Rudy Giuliani in New York, Bob Lanier in Houston, and Richard Riordan in Los Angeles. Even San Francisco in 1991 elected Frank Jordan, a middle-of-the-road Democrat and former police chief. In some cases, these pioneering mayors were followed by less groundbreaking but highly effective leaders like New York’s Michael Bloomberg or Houston’s Bill White. The resulting golden era of urban governance helped foster safer streets and more buoyant economies, attracting immigrants and a growing number of young and talented people to the urban core. Ironically, though, the urban revival fostered demographic changes that would make it much harder for these reform mayors to win today.

The new urban demographics have also occasioned a huge drop in civic participation in cities like New York and Los Angeles; in such Democrat-dominated cities, little motivation exists for any but the most ideologically driven or economically dependent voters to go to the polls. Bill de Blasio, for example, won the 2013 New York mayoral election with the lowest-percentage turnout since the 1920s, while Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti won reelection with only 20 percent of voters casting ballots—less than half of the turnout when Riordan won in 1993.

The electorate has not only shrunk but has also become demonstrably more left-leaning. In 1984, for example, Ronald Reagan garnered 31 percent of the vote in San Francisco, while winning 27.4 percent in Manhattan and over 38 percent in Brooklyn. By 2012, Mitt Romney, a more moderate Republican, won barely 13 percent of the vote in San Francisco, and he garnered less than half of Reagan’s share 28 years earlier in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Donald Trump did even worse in all these areas.

Cities today are about as politically diverse as the former Soviet Union; they are increasingly dominated by “the civic Left,” for which pragmatism and moderation represent weakness and compromise. The emergence of Trump seems to have deepened this instinct, with mayors such as de Blasio and Garcetti, Seattle’s Ed Murray, and Minneapolis’s Betsy Hodges all playing leading roles in the progressive “resistance” against the president. Their anti-Trump posturing is mostly for show, but these mayors are pushing substantive—and increasingly radical—agendas of social engineering. Their initiatives include, in Los Angeles, imposing “road diets” on commuters to reduce car usage (while making traffic worse), as well as “green-energy” schemes that raise energy prices. Most are committed to serving as “sanctuary” cities and enacting unprecedented hikes in the minimum wage in an effort to eliminate income inequality by diktat.

Many of these efforts clash with the aspirations of middle-class residents, who tend to drive cars, want to preserve their human-scale neighborhoods, and own small businesses highly sensitive to wage levels. Regulatory policies that seek to limit lower-density housing have led to escalating home prices in areas such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Portland. In these areas, housing costs (adjusted for income) are roughly two to three times higher than in places like Dallas, Atlanta, Charlotte, and Raleigh.

At the same time, high income taxes work against upper-middle-class entrepreneurs, who are usually stuck footing the bill for the “civic Left” playbook. These businesspeople often don’t have access to tax shelters, and they usually don’t earn most of their money through capital gains. Particularly vulnerable are those paying higher local income taxes, most of them living in and around the big coastal metros and the Midwest’s new basket case, Chicago.

No surprise, then, that many of those leaving California, New York, and other blue havens are people in their mid-thirties to early fifties—precisely the age when people are raising families, buying houses, and launching businesses. For many, an escape from the Left means heading to places where the political climate is, if not outwardly conservative, more moderate and business-friendly.

Nor is the progressive agenda likely to help its intended beneficiaries: the poor. The prospect of rapidly rising wages for mid-level jobs is undermining sectors like the Los Angeles garment industry, for example, where an exodus of employers is already occurring. Overall, as documented in a Center for Opportunity Urbanism study, economic prospects for minorities are much brighter in metro areas other than New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. This is particularly true for homeownership, where the rates for blacks are at least 20 percent higher in cities like Atlanta, Nashville, and Charlotte, compared with those more glamorous cities. Adjusted for income, homes are less than half as expensive for blacks and Hispanics in metropolitan Atlanta or Dallas–Fort Worth, compared with Los Angeles and the Bay Area. Meantime, heavily white cities with rising real-estate values like Portland, Boston, San Francisco, and Seattle are seeing what remains of their minority neighborhoods disappear.

Crime poses a conundrum for the new Left urban politics. The decline in crime in the 1990s reduced homicides dramatically, likely helping to reverse population loss in most cities. Now homicides are back on the rise in many large cities—but instead of bolstering law enforcement, most mayors have embraced the Black Lives Matter critique, which blames crime on institutionalized police racism. They do so despite measurable evidence that the main victims of this outlook, which has led to “de-policing” of vulnerable communities, are minorities and the poor.

Seattle, a city that has benefited mightily from the recent tech boom, epitomizes the tendency to pursue a left-wing agenda that undermines the very people it is intended to help. A city-funded University of Washington study found that Seattle’s minimum-wage increase actually reduced incomes and jobs for lower-wage workers. In a state with no income tax, Seattle’s city council unanimously passed a law that applies a 2.25 percent tax on income above $250,000 for individuals and above $500,000 for married couples filing together. Developers outside the city limits, such as in nearby Bellevue, are eager to accommodate the inevitable exodus of residents.

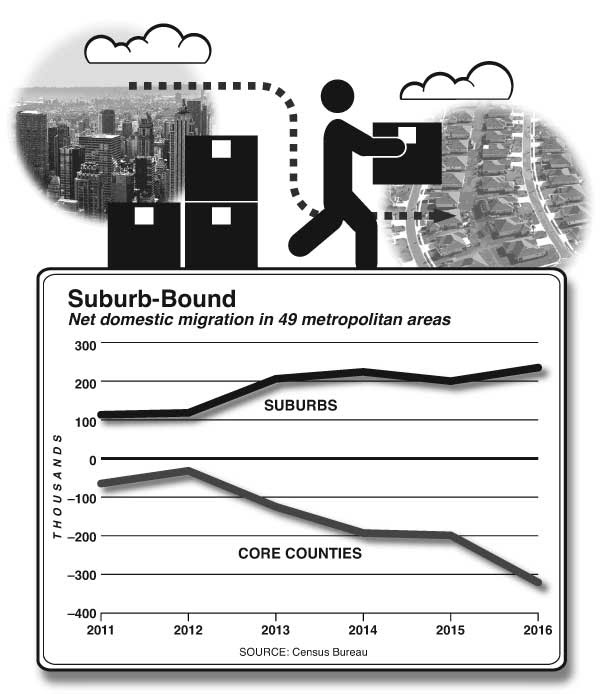

There is nothing inevitable about the future trajectory of urban economies. The suburbs, consigned to the dustbin of history by many urban boosters, have rebounded from the Great Recession. Demographer Jed Kolko, analyzing the most recent census numbers, suggests that most big cities’ population growth now lags their suburbs, which have accounted for over 80 percent of metropolitan expansion since 2011. Even where the urban-core renaissance has been strongest, ominous signs abound. The population growth rate for Brooklyn and Manhattan fell nearly 90 percent from 2010–11 to 2015–16.

The disposition of the millennial generation, on which so many urban dreams rest, will be critical. Roughly 70 percent of millennials already live outside core-city counties and, Kolko suggests, as they head into their thirties, many appear to be moving back to suburbia. USC demographer Dowell Myers suggests that we have reached “peak urban millennial” as the generation, albeit more slowly, becomes adult householders, not hipsters seeking a great “urban experience.”

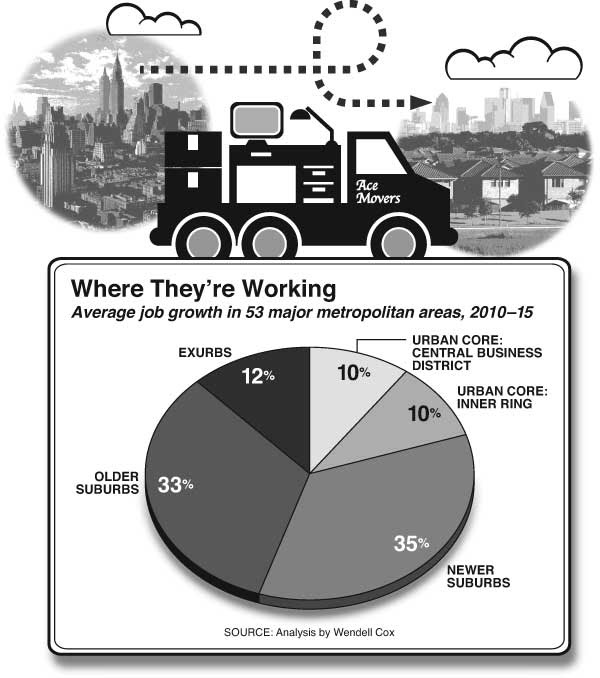

Economic trends follow a similar trajectory. Nearly 80 percent of all job growth since 2010 has occurred in suburbs and exurbs (see chart, page 45). Most tech growth takes place not in the urban core, as widely suggested, but in dispersed urban environments, from Silicon Valley to Austin to Raleigh. Despite the much-ballyhooed shift in small executive headquarters to some core cities, the most rapid expansion of professional business-service employment continues to happen largely in low-density metropolitan areas such as Dallas–Fort Worth, Nashville, and Kansas City.

And most young people are not doing well in elite cities. For example, in New York City, millennial incomes (ages 18–29) have dropped in real terms compared with the same age cohort in 2000, despite considerably higher education levels, while rents have increased 75 percent. New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco have three of the nation’s four lowest homeownership rates for young people and among the lowest birthrates.

Housing costs might be the biggest driver of millennial migration in the future. According to Zillow, for workers between 22 and 34, rent costs claim up to 45 percent of income in the Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Miami metropolitan areas, compared with closer to 30 percent of income in metros like Dallas–Fort Worth and Houston. This may be one reason, notes a recent Urban Land Institute report, that 74 percent of Bay Area millennials are considering a move out of the region in the next five years, while a recent survey by the UCLA Luskin School suggests that 18-to-29-year-olds were the group least satisfied with life in Los Angeles.

If the flight of moderate, middle-income homeowners continues, along with the growth in population of poor residents and childless hipsters, urban centers will be destined to serve as sandboxes for the progressive political class. Most urban leaders and media boosters have been slow to recognize such trends, which call for a thorough change in policy. Urbanist Derek Thompson suggests that cities like New York are wonderful for new immigrants, hipsters, and the ultrarich but “not a great place for middle class families.” Yet young families, not single hipsters, will now be increasingly critical to urban success.

Rather than indulging feel-good radical experiments in social justice, cities need to rediscover their historical role as creators of the middle class, as Jane Jacobs put it. If they don’t, some extraordinary areas—in brownstone Brooklyn, much of Manhattan, Seattle, west Los Angeles, and San Francisco—will likely become ever more exclusive, divided between the rich and the hip (many of whom are their subsidized children) and surrounding poor populations working in low-end services (or not working). The policy emphasis should shift to middle-income areas—whether in the Sunset district of San Francisco, Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley, Queens, or South Brooklyn—and closer suburbs, which could keep some younger families in the urban orbit. Such a shift will require a new kind of urban politics, one that encourages grassroots industries and corporate relocations that create more middle-income jobs, promotes the flourishing of human-scale neighborhoods, and accommodates families with good schools and low crime. The appeal of urban living remains viable, though today’s urban political class sometimes seems determined to kill it.

This piece originally appeared in City Journal.

Cross-posted at New Geography.