Lately we are often asked about the impact on pension costs from a stock market decline. Our answer might surprise you.

On December 31, 1999, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at 11,497. That fiscal year, the state spent $1.3 billion on pensions.

20 years later, the DJIA closed at 28,462. That fiscal year, the state spent $10.3 billion on pensions.

You read that right. As the stock market rose nearly 150 percent, state pension spending increased nearly 700 percent.

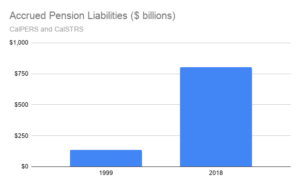

Too many people incorrectly believe that pension costs increase only when stock markets decline, but pension costs would rise even if the stock market never declined. That’s because pension liabilities accrete (grow) at the discount rate employed by pension funds for reporting obligations. The higher the discount rate, the greater the accretion. Because California’s pension funds discount pension liabilities at the same high rate at which they hope pension assets will earn, the state’s pension liabilities grow very fast:

If state pension funds earned their assumed rates of return, everything would work out fine. But, in an effort to keep employee contributions to a minimum, those pension funds assume unachievable rates that virtually guarantee high pension costs for governments down the road. For example, the rate assumed by California’s pension funds in 1999 implicitly forecast the DJIA to reach 28 million by 2099, as I described in a 2010 WSJ op-ed. Worse, in an effort to justify their unrealistic investment return assumptions, California’s pension funds tend to invest in riskier assets.

Market declines are temporary but lawmaker attention to pension issues must not be temporary. That’s because pension spending in California crowds out services at all times. E.g., the stock market quadrupled from 2009 to 2019 but state pension spending more than doubled over the same period, and that doesn’t count billions of supplemental payments authorized by elected officials.

Had elected officials acted on recommendations 15 years ago from me and other critics of the state’s pension funding at that time, pension costs would not be eating up school and government budgets today. But now it’s too late for those easy measures. State and local taxpayers have already stepped up to a 30 percent income tax increase and multiple parcel and sales tax boosts only to see new revenues hived off to rising pension spending. When elected officials are able to turn their attention from COVID, difficult steps will be required to protect services and taxpayers from this self-inflicted wound.

To answer the question posed at the top, lower market prices would lead to even greater pension spending, but because California’s pension funds tend to adopt amortization methods that defer shares of losses to future generations, the cost consequences would likely be spread over at least two decades.