Cross-posted at NewGeography.

UCLA’s most recent Anderson Forecast indicates that there has been a significant shift in demand in California toward condominiums and apartments. The Anderson Forecast concludes that this will cause problems, such as slower growth in construction employment because building multi-unit dwellings creates less employment than building the detached houses that predominate throughout California and most of the nation. The Anderson Forecast says that this will hurt inland areas (such as the Riverside-San Bernardino area and the San Joaquin Valley) because their economies are more dependent on construction than coastal areas, such as Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area and San Diego.

Detached Housing Permits Remain Strong in the Historic Context: The Anderson Forecast reports that multi-unit building permits have recovered more quickly than building permits for detached housing. However, any such shift is likely to be highly volatile. Since the peak of the bubble, the distribution of building permits between detached and multi-unit in California has been on a roller coaster. Indeed the Anderson Forecast characterizes the “2010 US Census” as “showing a significant shift in demand toward condominiums and apartments.” Actually, the 2010 US Census asked no question from which such a conclusion about housing types or any question from which such a conclusion could be drawn.

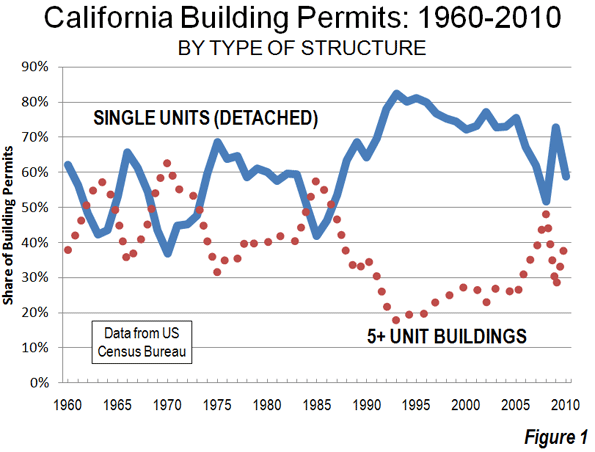

The trends in the building permit data are not completely clear. In 2005, the year before prices started to collapse, 75 percent of building permits in California were for detached housing. This trended downward, reaching a low of 52 percent in 2008. In 2009, the detached housing recovered to account for 73 percent of all housing building permits. Then the figure fell back to 59 percent in 2010.

With these erratic trends, it is tricky to forecast longer term market trends and consumer demand. Economic projections in 1934 would have suffered from a similar problem, as the Great Depression was continuing and no one could really tell when it would end. Today’s continuing housing depression may be similar.

Moreover, as the Anderson Forecast notes, detached housing construction declined in the early 1980s, dropping to 42 percent in 1985. In fact, over the 25 years between 1960 and 1985, detached houses accounted for an average of only 54 percent of new housing construction in California, well below the 2010 figure of 59 percent (Figure 1).

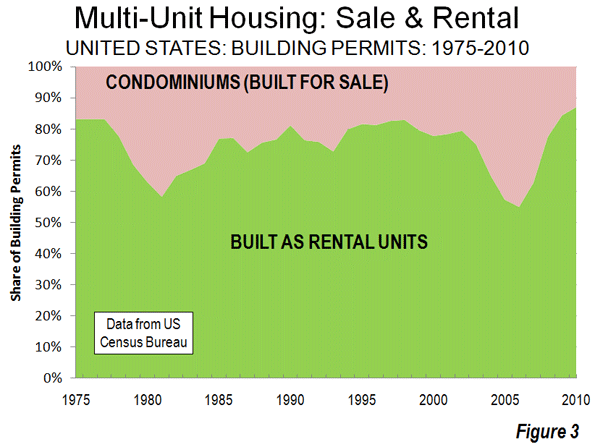

Equally important, the condominium market remains in a deep depression. In 2010, less than four percent of houses built for sale in the United States were multi-unit buildings, including condominiums (Figure 2), as an increasing majority of multi-unit buildings have been built as rentals (Figure 3). Comparable California data is not available, but from the peak of the bubble (2006/7) to 2009, there was a loss of more than 3,000 owner occupied multi-unit dwellings with 10 or more units, while owner occupied detached houses increased by nearly 100,000 (Note 1).

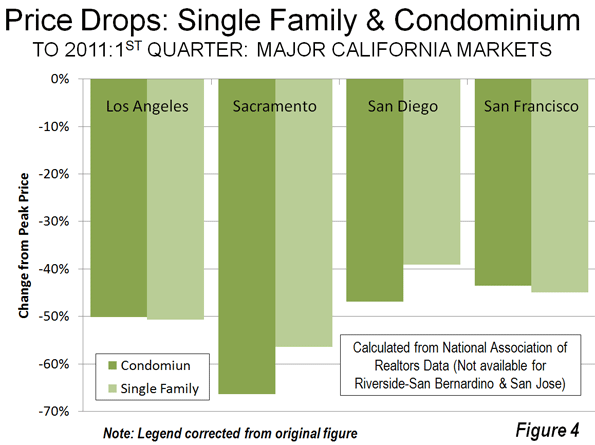

If there is an intrinsic pent-up preference for condominium living, it is not evident in the poor performance of high-density developments even in such theoretically desirable places as Santa Monica, San Francisco, Oakland, San Jose and North Hollywood. Condominium prices, for example, have fallen 52 percent in the major California metropolitan areas, compared to 48 percent for single-family houses (Figure 4). Naïve developers, relying too much on the much promoted notion that suburban empty-nesters were chomping at the bit to move to new housing in the core area, often watched their empty units liquidated at $0.50 or less on the dollar or turned into rentals. Further, if people are moving to apartments, it’s not for love of density but more likely due weakening economic circumstances.

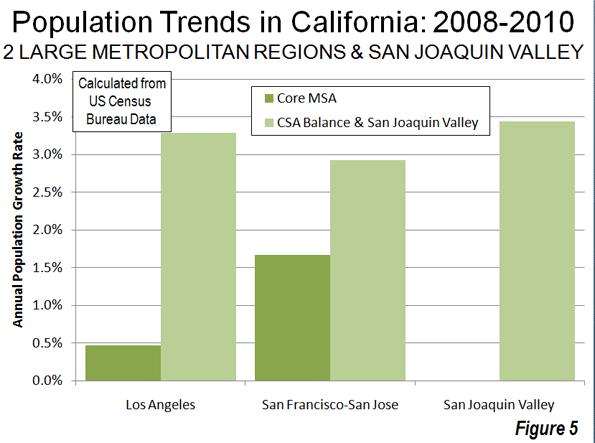

Inland California Continues to Grow Faster: The Anderson Forecast also suggests that growth in interior California will suffer because “workers are less likely to move inland into an apartment and commute toward the coast.” This assumption of slower inland growth reflects the conventional wisdom that areas outside the large coastal metropolitan areas have stopped growing since the burst of the housing bubble as people flock towards the coastal urban core (Note 2). The reality is different, as interior California and the peripheral metropolitan areas of the larger metropolitan regions (Note 3) continue to grow more strongly even in bad economic times. After the burst of the bubble, from 2008 to 2010 (Figure 5):

- In the Los Angeles area, the adjacent Riverside-San Bernardino (“Inland Empire”) and Oxnard metropolitan areas, combined, have grown at seven times the rate of the core Los Angeles metropolitan area.

- In the San Francisco Bay area, the adjacent Napa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and Vallejo metropolitan areas, combined, have grown nearly twice as quickly as the core San Francisco and San Jose metropolitan areas.

- California’s deep interior, the San Joaquin Valley has grown even faster than the exurban areas of Los Angeles and San Francisco.

One key reason: most people who move to interior areas do not commute toward the core. For example, less than 10 percent of workers in the Riverside-San Bernardino metropolitan area commute into Los Angeles County, a market share that declined 15 percent between 2000 and 2007. Many also simply cannot afford the higher cost of living in the coastal metropolitan areas, which likely will continue to retard growth in the core metropolitan areas.

The Policy Threat to New Houses : A survey by the Public Policy Institute of California suggests a vast preference (70%) for detached housing among the state’s consumers. This continuing preference is demonstrated by detached housing prices that are generally two times historic norms relative to incomes in the coastal metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and San Jose).

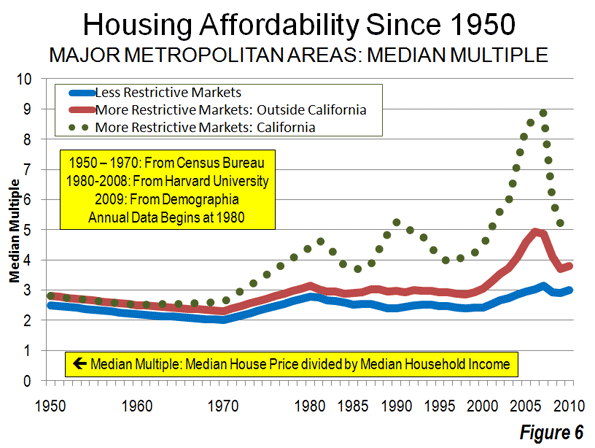

Yet now, this choice is under a concerted assault by both the state and many local governments, cheered on by most media and the academic community. For years, planning regulations have driven land prices so high that house prices have risen to well above the rest of the nation (Figure 5) under regulations referred to by terms such as “smart growth” and “urban containment.” The regulations and the inevitably resulting speculation propelled a disproportionate rise (nearly $2 trillion) in California house prices compared to national norm. If California house prices had risen at the same rate relative to incomes as in more liberally regulated areas, the loss to financial markets could have been hundreds of billions of dollars less when the bubble burst (Figure 6).

Planning for Crowding and Density: California’s assault on detached housing is taking on a distinctly religious fervor. The state’s global warming law (Assembly Bill 32) and urban planning law (Senate Bill 375) is providing a new basis to impose draconian limits on the construction of detached housing. For example, in the San Francisco Bay area, it has been proposed that 97 percent of new housing be built within the existing urban footprint. That would mean an emphasis on multi-unit housing and little or no new housing on the urban fringe. The option of a single family home will be all but non-existent for even solidly middle income Californians.

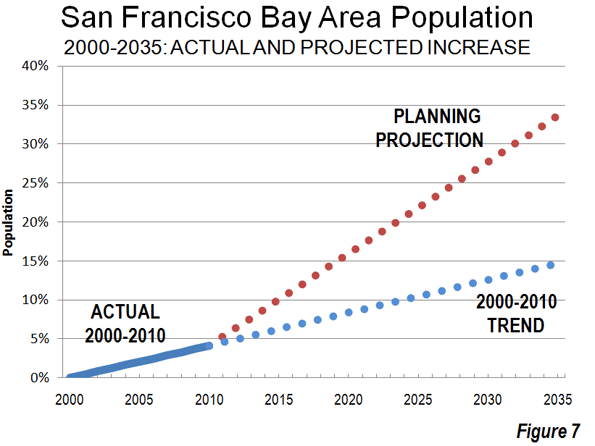

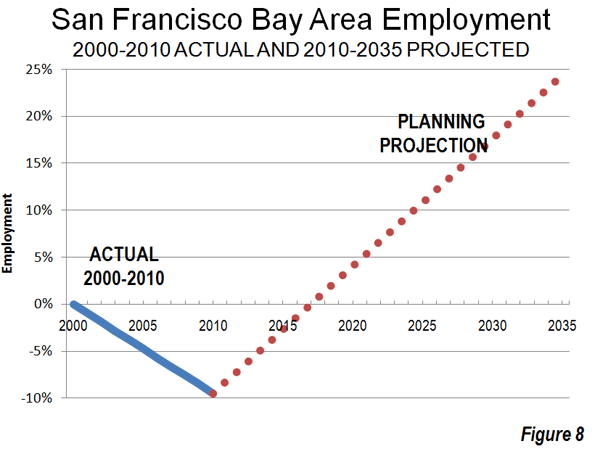

Planning authorities in the Bay Area seem oblivious to the fact that destroying affordability also destroys growth, already evident by the state’s poor economic performance and ebbing demographic vigor. Planners rosily project 2 million more people between 2010 and 2035 in the San Francisco Bay area. The growth rate over the past 10 years suggests a number less than half that (Figure 7) and given the rapid aging of the area, even this estimate may be too high. The planners also project more than 1.2 million new jobs, something difficult to believe given the more than 300,000 job loss (Note 4) that occurred in the Bay Area between 2000 and 2010 (Figure 8).

The Environmental “Fig Leaf:” The environmental justification for these policies is fragile . Research supporting higher density housing has routinely excluded the greater emissions from construction material extraction and production, building construction itself and common greenhouse gas emissions from energy consumption that does not appear on consumer bills. Further, higher densities are associated slower and more erratic speeds, which retards fuel efficiency and increases greenhouse gas emissions, a factor not sufficiently considered.

The report seems to ignore any other options besides rapid densification, which as McKinsey Global Institute has pointed out is not at all necessary to reduce GHG emission reductions. They point to other factors as more fuel efficient cars.

Oddly, the San Francisco Bay Area proposal does not even mention working at home (much of it telecommuting), the most environmentally friendly way of accessing employment. Working at home has grown six times the rate of transit since 2000 in the Bay Area.

Outlawing New Houses Detached housing remains the overwhelming choice of Californians. There is no indication that this preference is about to be replaced by a preference for high-density housing. Current and future middle class Californians could be corralled into more crowded conditions, because questionable planning doctrines mandate that detached housing should be outlawed.

—-

Notes:

1. Calculated from 2006, 2007 and 2009 American Community Survey data. The over ten unit category is used because is more generally reflective of the dense condominium development generally favored by densification advocates (Latest data available).

2. Another questionable tenet of conventional wisdom is that the price declines in the outer suburbs were greater than in the cores. When the price declines reached their nadir, core California markets were generally at least as depressed from their peak prices as suburban markets.

3. Metropolitan region refers to combined statistical areas, which have a core metropolitan area, such as the Los Angeles MSA and include surrounding metropolitan areas, such as the Riverside-San Bernardino MSA and the Oxnard MSA.

4. Annual, 2000 to 2010, calculated from California Economic Development Department data.